Victor Ayeni explores how mistaken bank transfers are increasingly affecting Nigeria’s cashless economy, with some recipients spending, hiding, or outright refusing to return money sent in error.

A Windfall Turns Sour

For Richard Okoye, a schoolteacher living on a modest salary, a surprise credit alert of ₦300,000 on his phone felt like a stroke of luck. The money had been mistakenly transferred into his account by his bank.

At first, he hesitated, suspecting an error. But excitement took over, and he quickly withdrew a large portion, spending it on postponed household items and a celebratory visit to a nearby pub.

Three months later, the bank contacted Richard to recover the funds. Threatened with police action and potential arrest, he had no choice but to refund the ₦300,000, learning the hard way that “found money” can have serious consequences.

The Risks of Fat-Finger Errors

On November 21, 2025, lawyer Ibrahim Lawal accidentally transferred ₦500,500 instead of ₦50,500 to a POS operator in Benin City, Edo State. Neither he nor the operator noticed at the time.

With help from friends and his account officer, Lawal eventually recovered ₦450,000 via a reversal, highlighting how errors in digital banking—often called “fat-finger” mistakes—can lead to significant financial stress.

A report by EdPlugNG (Nov 2025) found that nearly half of Nigerian banking users experienced losses due to interface-related mistakes in the past year. Many of these errors stem from app design issues, with figures entered incorrectly, wrong beneficiaries selected, or fatigue causing late-night mistakes.

Recipients Who Refuse to Return Money

Not all mistaken transfers are resolved amicably. Farouq Bello mistakenly sent ₦350,000 to the wrong account. The recipient, Abiodun, blocked him and only returned ₦50,000, ignoring repeated appeals and public pressure.

Finance analyst Caleb Ohaeri explains that while most mistakes are unintentional, recipients who refuse to return money after proper notification may be guilty of fraud. He advises immediate reporting to banks and, if necessary, escalation to courts.

Legal Implications

Lawyer Emmanuel Omirin notes that receiving funds in error is not inherently a crime, but refusing to return them is. Under Nigerian law, such behavior can constitute stealing or conversion of property, punishable by up to five years’ imprisonment and restitution.

Banks can also place a Post No Debit (PND) on recipient accounts to safeguard funds pending investigation. If the money is withdrawn or the recipient obstructs recovery, law enforcement may be involved.

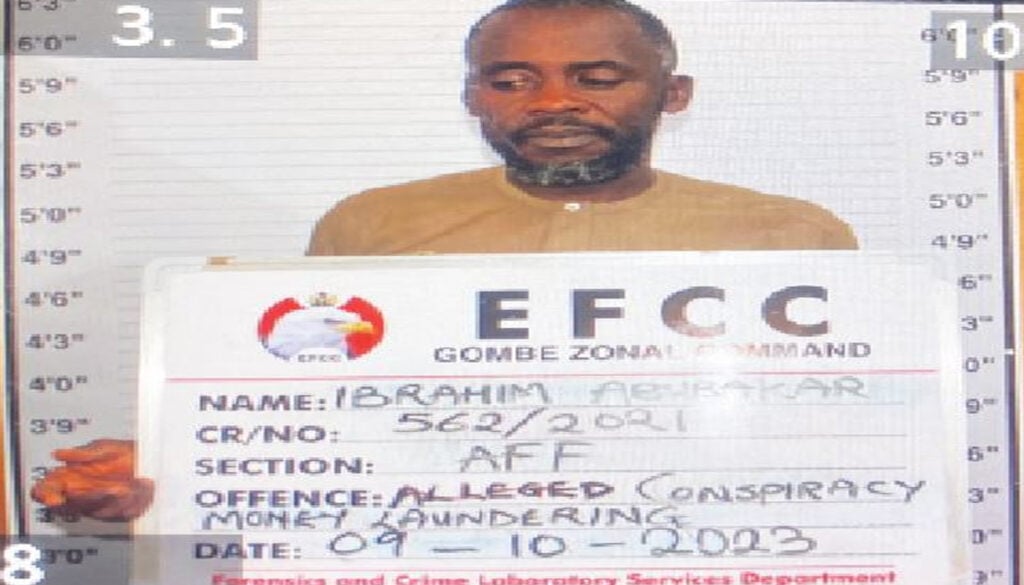

High-Profile Cases

Some recipients have faced prosecution:

Kingsley Ojo unlawfully spent ₦1.3bn mistakenly credited to him; he was sentenced to one year in prison or a ₦5m fine and ordered to return ₦272m to First Bank Plc.

Ibrahim Abubakar, a Plateau-based businessman, was arrested after spending over ₦57m transferred by mistake.

Haruna Samuel, a Nigerian Air Force officer, allegedly used ₦20m erroneously credited to him, facing theft charges.

Meanwhile, there are examples of integrity: Aisha Yelwa, a petty trader in Lapai, Niger State, returned ₦330m mistakenly credited to her account, despite personal financial pressure.

Advice for Nigerians

Experts advise:

1. Double-check recipient details before confirming transfers.

2. Report errors immediately to your bank, providing all transaction details.

3. Consider legal routes if the recipient refuses to return funds, including court orders or inter-bank mediation.

4. Stay calm—rash withdrawals or confrontations can complicate recovery.

With Nigeria’s digital banking ecosystem expanding rapidly, vigilance and prompt action are crucial to prevent accidental transfers from becoming financial disasters.