German leaders often declare, “Work must be worth it.” Yet, despite this mantra, an increasing number of full-time employees in Germany are relying on state support — a trend that has reignited criticism over the country’s minimum wage policies and broader labor market inequalities.

Merz Pushes Welfare Reform

Chancellor Friedrich Merz addressed the Bundestag this week, stressing the need to reform the Bürgergeld, Germany’s unemployment benefit system. Speaking in his typically direct tone, Merz emphasized that hard work should be rewarded and performance-based pay reinstated. “People in Germany must be able to see that their effort pays off,” he declared.

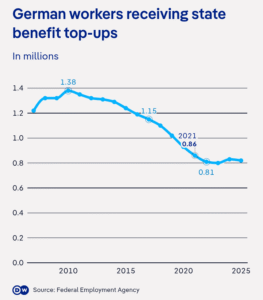

However, his message was somewhat undermined by newly released statistics. In 2024, approximately 826,000 working individuals were reliant on Bürgergeld — about 30,000 more than the previous year. This marks the first rise in such figures since 2015, the year Germany introduced its first minimum wage.

Back then, more than a million workers still needed welfare support. That number had been declining — until now. In 2024, these top-up benefits cost the state nearly €7 billion, up from €5.7 billion in 2022.

A Wage Too Low?

Cem Ince, a member of the socialist Left Party, who requested the data from the government, called the situation “unacceptable.” He told *Deutsche Welle*: “We’re subsidizing low wages and allowing exploitation to continue.”

The minimum wage was significantly increased in early 2023 to €12 per hour, but since then, it has only climbed modestly to €12.82. On Friday, Germany’s minimum wage commission — made up of representatives from trade unions and employers’ associations — announced incremental increases: €13.90 in 2026, and €14.60 in 2027. This falls short of the €15 target proposed by the Social Democrats (SPD).

Helena Steinhaus, founder of the anti-poverty group Sanktionsfrei (“Sanction-Free”), criticized the small hikes, noting they lag behind living cost increases. “Rent alone rose by 4.7% last year nationwide — and up to 8.5% in Berlin. No wonder more workers need to supplement their income,” she said.

Full-Time vs. Part-Time: A Deeper Divide

However, some economists argue the root issue isn’t wages — but working hours. Holger Schäfer of the German Economic Institute (IW) pointed out that most benefit recipients aren’t full-time workers. “The problem isn’t low hourly pay; it’s low hours,” he said.

Indeed, only 81,000 of the 826,000 benefit recipients in 2024 held full-time jobs. Many others were trainees, part-timers, or caregivers.

Yet Ince contends this doesn’t justify insufficient pay. “The current minimum wage is a poverty wage. Even full-time workers can’t afford housing in half of Germany’s major cities,” he said.

The Role of Childcare and Structural Barriers

Many individuals work part-time because of childcare responsibilities, a challenge compounded by limited nursery and preschool access. The IW estimates that 306,000 children under age three in Germany currently lack legal childcare spots. A 2021 study from the Institute for Employment Research (IAB) confirmed that more children in a household significantly increase the likelihood of parents needing state assistance.

Ince argues that expanding childcare infrastructure would free many from part-time constraints and dependency on welfare. “We must tackle the root causes, not blame individuals.”

Employers Push Back Against Wage Increases

Despite growing demand for higher wages, Schäfer warned that raising the minimum wage too much could backfire, as companies might reduce hiring due to increased labor costs.

But Steinhaus remains skeptical of this argument. “Employer groups have used this excuse for over a decade — and it hasn’t held up. Most businesses actually benefit from low labor costs, but society pays the price.”

What’s Next for Merz’s Reforms?

Schäfer also downplayed the latest data, arguing that the uptick in benefit recipients may reflect broader economic conditions rather than a reversal of positive trends.

Nonetheless, Chancellor Merz appears committed to overhauling the welfare system to push more people into work. But critics, like Steinhaus, argue his approach is misguided.

“When Merz says, ‘work must be worth it,’ he’s talking about cutting benefits, not raising wages,” she said. “But that only pits the working poor against the unemployed. The real solution is ensuring people earn enough to live with dignity.”