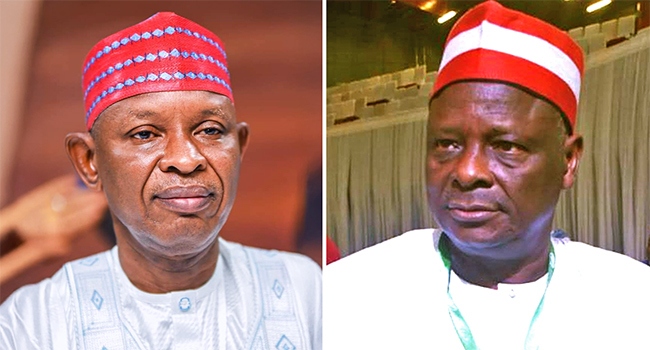

From Rimi to Yusuf: Kwankwaso and Kano’s Recurring Narrative of Political Betrayal.

The claim by Senator Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso that he “helped” Governor Abba Kabir Yusuf by reaching out to Supreme Court judges during the 2019 Kano election crisis is not only politically explosive — it is also deeply ironic.

Kwankwaso, reacting to Yusuf’s reported defection, recounted that after the 2019 governorship election was declared inconclusive, he personally went to the villages of Supreme Court justices seeking judicial intervention, portraying Yusuf’s departure as betrayal.

But beyond the impropriety such a statement suggests, the larger political question is this: can Kwankwaso credibly occupy the moral high ground on “betrayal”?

The Rimi Precedent.

Grassroots political memory in Kano has long preserved the bitter fallout between Kwankwaso and his early benefactor, the late Alhaji Abubakar Rimi. Rimi was instrumental in building the political machinery that facilitated Kwankwaso’s rise in 1999.

Yet once Kwankwaso assumed office, many within Kano’s old political establishment contend that he dismantled Rimi’s structure and sidelined the very coalition that produced him. Many attribute that act of betrayal by Kwankwaso to Rimi’s depression which led to his demise. Abubakar Rimi never recovered from the betrayal of Kwankwaso.

That episode remains one of the earliest and most cited examples of the “Kwankwaso paradox”: a leader who demands absolute loyalty but is accused by associates of routinely severing alliances once power is secured.

The Atiku Episode: February 23, 2019

The pattern resurfaced nationally in the 2019 elections. Multiple political actors, including sitting lawmakers, have accused Kwankwaso of abandoning Atiku Abubakar during the February 23 presidential contest after securing his own calculations in Kano.

The House Minority Leader, Ali Sani Madaki, recently described Kwankwaso’s posture as hypocritical, arguing that a man with such a record lacks credibility branding others as betrayers.

Godfatherism and Political Ownership.

Kwankwaso’s framing of Yusuf’s defection reflects a deeper problem in Nigerian politics: the belief that electoral mandates are privately owned by political patrons rather than constitutionally held by the people.

In mature democracies, political mobility is judged by ideology and governance performance.

In Kano’s godfather model, however, it is often reduced to loyalty oaths and personal ownership of structures.

Kwankwaso’s grievance is therefore less about principle and more about political control — the loss of a protégé who has now chosen independence.

The Irony of the Accusation.

It is difficult to accuse another of betrayal when one’s own political history is repeatedly shadowed by similar allegations — from Rimi, to national alliances, to internal party fractures over decades.

If anything, Yusuf’s defection may simply represent what Nigerian politics has always been: fluid, transactional, and rarely sentimental.

Kwankwaso’s public lament may resonate emotionally, but history suggests it is unjust to present himself as the sole victim of betrayal in Kano’s complex political evolution.

Headlinenews.news Special report.