Long hailed as the king of Afrobeat, the late Nigerian music icon Fela Kuti is finally being honoured by the global music industry. The legendary musician will posthumously receive a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Grammys, nearly three decades after his death at 58.

“Fela has lived in the hearts of the people for so long. Now the Grammys have acknowledged him—it’s a double victory,” said his son, musician Seun Kuti, in an interview with the BBC. “It brings balance to Fela’s story.”

Rikki Stein, a longtime friend and manager of Fela, described the recognition as “better late than never,” noting the historical underrepresentation of African artists on such platforms.

The award coincides with a broader recognition of African music globally. Following the international success of Afrobeats—a genre inspired by Fela’s pioneering sound—the Grammys introduced the Best African Performance category in 2024. Nigerian superstar Burna Boy is also nominated this year in the Best Global Music Album category.

Fela Kuti will make history as the first African artist to receive a Lifetime Achievement Award posthumously, joining the ranks of other legends such as Carlos Santana, Chaka Khan, and Paul Simon. His family, along with close friends and collaborators, will accept the award on his behalf.

“This is about more than just my father—it’s about recognition for humanity,” Seun Kuti said.

Stein emphasised Fela’s legacy as a champion for the underprivileged, criticising social injustice, corruption, and governmental mismanagement. “You cannot ignore that aspect of his work,” he said.

Fela Kuti was more than a musician; he was a cultural theorist, political activist, and the architect of Afrobeat. Alongside drummer Tony Allen, he fused West African rhythms with jazz, funk, highlife, extended improvisation, call-and-response vocals, and politically charged lyrics.

Over a three-decade career, he released over 50 albums, blending music with ideology and rhythm with resistance. His outspokenness drew the ire of Nigeria’s military regimes. Following the 1977 release of Zombie, a satirical critique of soldiers, his Lagos compound, Kalakuta Republic, was raided, residents brutalised, and his mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, later died from injuries sustained during the attack.

Fela responded defiantly, turning grief into protest through music, notably with Coffin for Head of State, and cementing his role as a fearless advocate for liberation, pan-Africanism, and African-rooted socialism.

Born Olufela Olusegun Oludotun Ransome-Kuti, he dropped “Ransome” due to its Western connotations. In 1978, he staged a widely publicised marriage ceremony with 27 women, who became partners, performers, and co-architects of Kalakuta Republic’s communal vision.

Despite repeated arrests, beatings, and censorship, Fela’s influence only grew. Stein reflects: “He wasn’t doing it for awards; he was about freeing minds. He was fearless and determined.”

Fela’s musical development was shaped by Nigeria and Ghana. Highlife music from Ghana’s ET Mensah, Ebo Taylor, and Pat Thomas influenced his early direction, blending melodic guitar lines, horn arrangements, and dance rhythms into the Afrobeat sound that would define him.

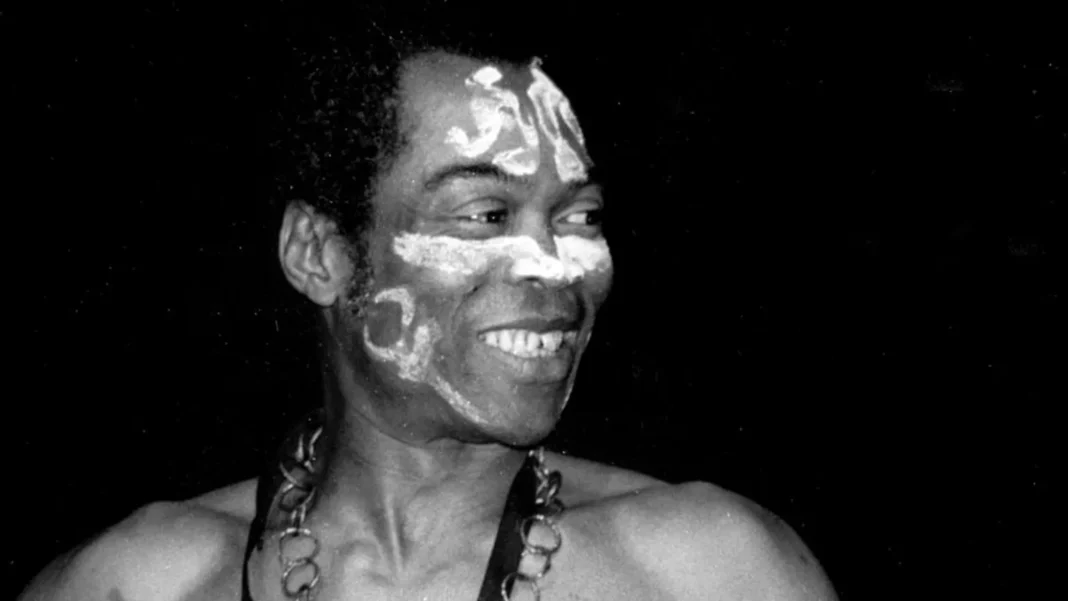

On stage, Fela was unmistakable—bare-chested or in vibrant West African prints, hair in a crisp Afro, saxophone in hand, leading a band of 20+ musicians. His performances at Lagos’ Afrika Shrine were part concert, part political rally, and part spiritual ceremony. “When Fela played, the audience wasn’t separate—they were part of it,” Stein recalled.

His visual identity, shaped by artist Lemi Ghariokwu through 26 album covers, remains iconic. Today, Fela’s music continues to inspire millions globally and informs the work of artists like Burna Boy, Kendrick Lamar, and Idris Elba, who curated an official Fela Kuti vinyl box set.

Seun Kuti, who was 14 at his father’s death, reflects on his upbringing: “Fela never made me feel like a child. He was open, honest, and grounded. He belonged to himself, but we belonged to him.”

Fela led multiple ensembles, most notably Africa 70 and later Egypt 80, trained in discipline, endurance, and ideological purpose. Stein notes Fela’s meticulous attention to detail: “He tuned every instrument personally. Music wasn’t entertainment—it was his mission.”

The Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award serves as a global acknowledgment of Fela Kuti’s enduring impact on music, culture, and political consciousness, cementing his place as a true icon of African artistry.